My father flew 36 missions over Europe during World War II before he was 20 years old. He lived for 81 years, yet rarely talked about his service as a U.S. bombardier. I learned everything I know about the war studying books, documentaries, music, and movies. But one thing I did know was that my dad flew two different types of planes—a B-24 and a B-17 Flying Fortress.

The closest I'd ever gotten to the latter was when I saw "Shoo Shoo Shoo Baby," a permanently grounded B-17 belonging to the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. But last month, an airworthy B-17 (one of only nine left in the U.S.) was taking off less than 20 miles away from where I lived. I sped over there and got a seat.

It was a beautiful, crystal-clear day. Perfect for flying. The aircraft was gorgeous—all rivets, slabs of naked, shiny metal with guns aplenty. This is a mighty machine born of sheer raw muscle, ingenuity, and urgency. Seventy-three years later, it's still a beautiful sight to behold.

The Birth of the Flying Fortress

Boeing designed the B-17 in 1934 as part of the competition to replace Keystone biplane bombers, planes whose DNA remained mired in World War I design. The U.S. Army Air Corps (as it was called at the time) needed something faster—and deadlier.

A team of Boeing designers produced the earliest version of the B-17, called the "Model 299," and on July 28, 1935, the plane took to the skies and began breaking records, making a non-stop 9-hour flight from Seattle to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio, with a speed of 232 mph. When Richard L. Williams, a Seattle news reporter, saw the Model 299, he called it the "Flying Fortress." The name stuck.

Unfortunately, after logging only 40 flight hours, the 299 crashed due to a failure to disengage the elevator gust-lock. Even so, the U.S. ordered 13 planes. As the names and numbers changed with each model refined, tested, and produced, the plane's reputation grew.

The B-17 was still thought of as a big, complicated, and expensive weapon, though. But as Europe inched toward war in the late 1930s, President Franklin Roosevelt asked Congress for $300 million to buy 3,000 of the planes for the Army Air Corps. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, new models had to be hastily designed, manufactured, and delivered, with some suffering from faulty machine guns, oxygen problems, and other defects. Modifications were made with each new batch of planes, and production was massively ramped up after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Once the U.S. officially entered the war, the B-17 became a bomber for the U.S. Eighth Air Force stationed in England. Bombing raids happened during the day for better visibility and more precise targeting, but insufficient cover resulted in initial heavy losses of both crew and aircraft. In time, as refinements were incorporated along with better crew training, the B-17 achieved its now legendary status as a plane that could dish it out and take it, too.

A typical European flight would begin with the men waking at dawn, having breakfast, donning their gear, and climbing to 25,000 feet, where the temperature in the plane could fall to as little as -56 degrees Fahrenheit. As their target approached, the bombardier took control of the craft, using his Norden bombsight to pinpoint targets. Upon the final release of the bombs, the plane would then turn around head for home, sometimes sustaining an incredible amount of damage. A flight crew on a B-17 had a low chance of survival and plenty of them never returned. More than7,100 B-17s and 26,000 men were lost during the war.

After the war, the U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF) still had thousands of B-17s, now already out of date as new innovations continued to streamline military aircraft. A few remained in duty for VIP transport, photo reconnaissance, and air-sea rescues, but most ended up melted down at either the Kingman Army Air Field in Arizona or Walnut Ridge Army Air Field in Arkansas.

The Planes That Survived

Out of the 12,731 B-17s produced, only a dozen are in flying shape today with many more stowed in museums or in various stages of refurbishment around the world. The one I'm flying was originally called "Chuckie," but upon restoration was dubbed the "Madras Maiden" after its Oregon hometown. Now it's also part of a nationwide tour by Liberty Foundation, who hopes to keep history alive by offering B-17 rides to the public.

Lockheed-Vega built and delivered what would become the Madras Maiden to the USAAF on October 16, 1944, but it never saw combat. Instead, it was used as a training unit during and after the war, then finally dropped from the Air Force's inventory in May 1959. From then it performed a series of odd jobs, whether hauling freight or spraying crops, until it eventually landed in the Military Aviation Museum in 2009. After being purchased in 2013 and undergoing restoration, the Liberty Foundation stepped in and finished the job.

"We have so many families coming who want to see what dad or Grandpa did," says Scott Maher, Liberty Foundation Director of Operations. "And sometimes they bring them with them. It's wild – sometimes the veterans can't remember what they had for breakfast, but they remember every last detail of what happened in combat."

Stepping inside a B-17 as it rests on the Rocky Mountain Airport tarmac, it's hard to imagine how ten airmen could fit inside and fly nine hours straight. Getting to the cockpit requires a full sideways turn, followed by a squeeze-through so tight that a heavy lunch would make it difficult. To reach the bombardier station below, the pilot needs to briefly crawl on hands and knees, and there are plenty of places to bash your head if you get caught gawking.

But beyond its jam-packed interior, this piece of World War II engineering commands quiet awe. You're in the belly of a legendary weapon whose only purpose was to annihilate while withstanding anti-aircraft fire, flak, and heavy machine gun fire. The U.S. dropped 640,000 tons of bombs on Nazi Germany alone during World War II, and the B-17 and its pilots—men like my father—are who dropped them.

Some of the most ferocious pieces of equipment on the B-17 are the .50-caliber machine guns on each side of the waist, and there are a total of 13 of them in the front, back, and underneath. There is also the famous "Norden Bombsight," a primitive analogue computer used for accurate bombing after the bombardier entered data like altitude, atmospheric conditions, airspeed, ground speed, and drift.

This is what my dad looked through before calling "bombs away."

This unit was so top-secret that it would only be loaded onto the plane by armed guards at the last minute and removed after landing. It also included a self-destruct mechanism should the plane go down, and crew members had to take an oath to protect the bombsight with their lives.

At the right of the plane, near the door lying on its side, are one of the 500-pound bombs typically dropped on missions. It may be a dummy, but its mere presence is sobering.

A Fortress Takes Flight

I take my seat behind the co-pilot, and the engines whirl to life. The plane's interior becomes incredibly noisy, despite the offered earplugs. One has to shout to hear and be heard. Finally, it's "off we go, into the wild blue yonder."

At our altitude of 2,000 feet, the cold is formidable, but nothing compared to the temperatures World War II airmen experienced. As the flight continues, I'm wondering what I would do—how I would act—if I were flying over 1943 Europe with a belly full of explosives. I think of what my dad used to say: "We had a job to do. It was war."

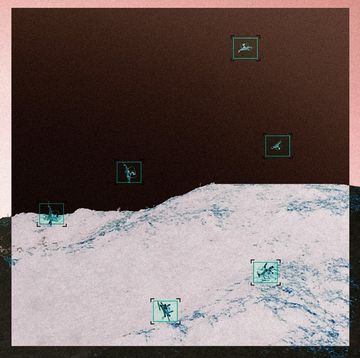

The flight is only about 40 minutes long but it feels like hours as I take in every possible detail with my eyes and my Nikon. My fellow passengers and I can barely speak over the noise, so we stop trying.

A middle-aged woman roams the plane with an 8x10 framed photo in her hand—a photo of her late father, a WWII gunner. Her eyes are full of tears after a few minutes into the air. The other passengers are stonefaced— there are no smiles or celebration. Instead, it's impossible not to think of how many teenagers and young men went up in the thousands of planes just like this and never came back. His whole life, my father said he would get through tough times by saying to himself, "If I can get through the war, I can get through this."

Now, I have a tiny sliver of an idea what he was talking about when I put my hands on the machine gun he fired at the Lutwaffe or glance through the Norden bombsight. I also see the door he and his crew had to jump out of when returning from a mission, when his plane ran out of gas in the English fog. I am lucky to be alive, because he was lucky to be alive.

Eventually, the Madras Maiden lands and rolls roughly to a stop. No one says anything – there isn't anything to say.

I'm stunned, fascinated, and obsessed by the B-17 and the experience. I drive home shaken, sleep for two hours, return at sundown for more photos, then a third time the next day for even more. I want to burn the experience into my memory. In between shoots and ever since my flight, I read and feverishly study documentaries all about the B-17 and the men who flew in them. I now hold my father in a new esteem because he flew three dozen missions and never said more than a few words about it.

The B-17 Flying Fortress is more than just guns, engines, and metal—it's a flying reminder of a generation of sacrifice.